|

There

are a certain number of precautions that must traditionally be taken before

one actually starts a matanša

(pig killing) on Eivissa. Killing a pig on a Friday or a Sunday is to be avoided: these

beliefs are, of course, tied in with Christianity, and the Sunday ban was particularly

strong and 'policed' on Eivissa in

past centuries by the much-feared Office of the Holy Inquisition. We have spoken

before about the absolute ban on any women touching anything to do with the

matanša if they had their monthly

menstruation at that particular time: this traditional prohibition is one of

the strongest, even today. It should also be noted that traditionally pagesas

eivissencas (Ibicenco peasant women) should not plant or harvest, cook food

or paint houses (another traditional female activity) during the time of their

menstruation either. Certain female readers in the UK or the USA may think that

these prohibitions are a sign of cultural 'backwardness' or an indication of

males 'putting women down', but they would be wrong. Almost every single culture

in the world has - or had - similar types of restrictions relating to female

activities during the time of menstruation, it is just that our so-called 'modern'

Euro-American cultures have (relatively recently) forgotten them. In most traditionally

oriented societies (and these are still in the majority in the world today,

not in terms of population numbers but in terms of numbers of cultures - we

should always bear in mind that our modern Euro-American string of cultures

form a distinct minority in the world family of cultures) the monthly time of

menstruation can in fact be a welcome form of rest for women as they, depending

on their particular culture, usually have about one week per month free from

doing some of the most drudging female chores. On the island of Ambae in northern

Vanuatu in the southwestern Pacific isolated comfortable huts on stilts were

built in a restricted area in the jungles away from the villages. Each of these

huts were the regular temporary abode of a recognized group of women during

their menstruation, and the time spent as a group each month in this hut was

treasured as a relaxing time away from drudgery and a time to catch up on conversation

and gossip. Many hard-working female executives in New York might sometimes

wish there were similar facilities for them!

There

are, of course, traditional belief systems concerned with potential 'pollution'

at such critical times as planting crops - many cultures believe that crops

will not grow well if planted by a woman during her menstruation. The same pertains

to food preparation and many other activities, and such beliefs are almost world-wide.

On the isolated western coast of the island of Santo in northern Vanuatu are

a small number of villages that have the traditional right to make pottery.

There, pottery making is an activity restricted to women and it is a seasonal

activity that usually takes place around May/June each year. However, women

are forbidden to take part when they have their periods, it being believed that

the pots will crack during firing or will be weak and can leak if this prohibition

is not followed. In the west coast Santo village of Wusi this prohibition began

to break down in the early 1960s and pots since then have been much weaker and

very easily broken (which may be due to the fact that modern metal pots and

saucepans began to be more easily available in the area around that time, and

thus less care was taken in traditional production). Whatever the actual reason,

it is said that the relaxation of the menstruation 'taboo' is the real reason

for the loss in quality. Ibicenco peasants have similar attitudes to menstruation:

it is often believed here on Eivissa

that a child that has been born weak and grows up to be a weak individual is

sometimes so because the original conception took place within only a few days

of the mother finishing her monthly period. Menstruation prohibitions in the

'modern' world do not count for much, at least to the general public, who either

know nothing about them or think that they are a relic of the past: not so,

though, to certain computer companies (As mentioned in my first article about

pigs) who may employ women in the manufacturing sections related to computer

chip etching. Here, women are either asked not to do this delicate etching work

during their menstruation or to wear special gloves, a policy not publicized

by these companies but one they believe essential to the production of properly

functioning chips. Certain chemicals that women secrete from the sweat glands

in their hands at this time are suspected to interfere, at least in this case,

with production. Such attitudes may be considered by some to not necessarily

be 'politically correct', but when potentially billions of dollars/pounds are

at stake these considerations take second place.

Non-material

aspects are also of importance during the first stage of an Ibicenco pig killing

- none of the men holding the pig on the banc de matar (pig killing bench), nor the matanšer (the traditional

pig killer with the knife) nor the special woman standing nearby with the bowl

to catch the first blood from the jugular vein must say (or even think) anything

that is not respectful of the pig about to be killed. A thought or a comment

such as 'This is not much of a pig' or, as would be a typical comment in such

a situation in England, 'Oh, the poor creature', is to be completely avoided,

otherwise the pig will not die quickly and cleanly but will have a difficult

death. Similar attitudes exist in certain pig-killing cultures in Vanuatu where

the pigs dying noises can be ritually admired to ease the death process. There

are physical aspects as well on Eivissa that must also be considered: it is not considered proper

for certain types of mancus (disabled people, those with missing fingers, or

a missing hand, arm, foot or leg: the origin of the term may possibly, as in

Italy, be related to an early word for 'stump'), to take part in a matanša

or in the subsequent associated 'embutido' production. The presence of such

people 'in the production line' could result in malformed 'embutidos', it is

thought.

'The

Devil's Piglet'. On Eivissa traditionally

there was/is, in some areas, an interesting attitude to the erišo

(hedgehog) at the time of matanšes.

If an erišo was seen somewhere near the place of the pig killing it was

considered by some as a bad sign, a sign of the presence of 'Satan', some say.

This contrasts with normal pagŔs eivissenc

(Ibicenco peasant) attitudes to the hedgehog, which was considered a delicacy

although involving a rather complex cooking procedure in baked earth/clay to

remove the spines (and numerous fleas). Erišo

meat tastes very similar to pig, quite succulent but with less fat. In early

Christian mythology on Eivissa though,

Saint Anthony (Sant Antoni Abad, from

whom San Antonio gets its name) was given a small pig by the Lord (the Famous

statue of Sant Antoni i es porquet - Saint Anthony and the piglet - or Sant Antoni des porcs - Saint Anthony of the pigs - is in the church

in Santa AgnŔs/Santa Ines in the Northwest

of the island). This gift of a piglet made the Devil extremely jealous and envious,

and he tried ways to get one too. However, the Lord gave him an animal that

tasted similar, but was small, slightly ugly and covered in sharp spines, the

hedgehog, 'the Devil's piglet'.

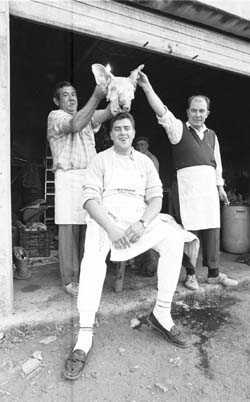

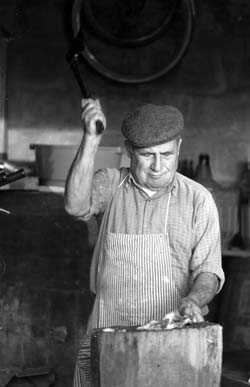

Whoops,

by now readers may have realized that I have been digressing a little from the

planned progression of articles relating to matanšes,

the traditional seasonal pig killings on Eivissa/Ibiza:

this week I should really have been dealing more in detail with the cutting

up of the pig and the preparations of the sausage-like sobrassada, botifarro

and botifarra so beloved by the local population. One will have to continue

this next week in more detail, although our editor Gary Hardy has already scanned

a number of his relevant photographs of such preparations to include in this

week's issue. But hopefully by now readers may have begun to suspect that the

topic of pigs on Eivissa/Ibiza is

not just the straightforward description of what types of food can here be made

from them. Here the topic of pigs leads one in to history, local mythology,

cultural gastronomy and a non-ending topic of conversation amongst the rural

population. Since 1973 I have spent a total of approximately 17 years pursuing

anthropological and cultural work in the fascinating cultures of the chain of

islands in the south west Pacific now known as the Republic of Vanuatu (and

a total of 32 years working on Vanuatu material from 'the outside'), where the

'cult of the pig', of many types and forms, reaches its worldwide climax. The

83 inhabited islands of Vanuatu form an incredibly complex series of interrelated

languages and cultures bound together by ritualized respect for ancestral (and

other types of) spirits and interlinked by a sort of 'pig internet' that joins

cultures, clans, lineageĺs, families and individuals together into a spiritual

timeworld that flows from the past through the present to the future and the

World of The Dead. Of course there is no cultural relationship between the cultures

of Vanuatu and that of the pagŔs eivissenc

(Ibicenco peasant), but it is certainly a great personal pleasure to be living

on an island (Eivissa) where one can

sit down with amics eivissencs (Ibicenco

friends) and 'talk about pigs until the sun comes up'. In fact one can be 'feliz

com un porc en su merde', as 'happy as a pig in its shit' on Eivissa,

if one really knows what the island is all about and one respects traditional

elements of the culture, such as the pig. Honoured guests coming to stay in

my ancient house here are given the bedroom that was originally the pig room

- although sometimes it takes a bit of explaining as to why it should be considered

an honour! Like Vanuatu, Eivissa is

always a bit of an eye-opener to those who want to have a broader view of life.

Here I am not talking about the Ibiza world of discotheques, dancing and drugs,

'etc', a world which is not Eivissa

but which has sadly damaged the traditional culture here to such an extent that

it may no longer exist except in memory by the time the young children of today

reach the age of their surviving grandparents. And when that time comes, Western

Europe's last surviving archaic, pre-feudal, culture - that of the pagŔs

eivissenc - will have disappeared forever. So I hope readers will forgive

me these cultural digressions, we are following a slightly different cultural

timetable here and are taking quick peeks at an ancient and vanishing culture

- and each peek needs to be savoured.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| All pictures

© Gary Hardy (January 1991) |

|