|

The

photo of a bee sitting upon a flower, licking its nectar, is probably

the most familiar image that we all have of bees.

Only

beekeepers see the bees in the first half of their life, the first three

weeks, when they live and work inside the hive.

Only

then do the bees fly outside the hive, first for two or three days, as

guardians of its entrance, then and for the rest of their life, as

pollen, water and nectar collectors. (This they will transform into

honey with the help of some body fluids)

It

is during this period of about twenty-five days when they become

familiar to us. (Only the bees that reach the end of the harvest season,

at the beginning of the winter, and spend the cold season feeding

themselves with their stocks of pollen and honey, sheltered inside the

hive, without having to use most of their energy, can survive till next

spring, up to six months, all together, at the most).

But

the really most important job that bees do when they sit upon a flower

is not collecting this rich and sweet aliment for us, greedy humans.

Since before we even appeared on Earth, a very large number of plants

have been using these insects as “Cupid”, as messengers in their love

affairs, as a very effective way, sometimes the only way, for their

reproduction, like artificial insemination, so common in our modern

times.

I’m

talking about pollination; the way complete plants (Phanerogams) use the

fecundation of their own seeds for reproduction.

Pollination, passing the pollen produced in the stamen (the masculine

organ of the flower) to the stigma (the female) that receives the

pollen, situated on the top of the pistil, and from there to the

ovaries, where the seeds are fecundated by it) is done by different

forms: Auto-pollination, when everything happens in every single flower

or in different flowers of the same plant, directly without needing any

outside help, or just by the wind (Anemophillas flower). (There is also

pollination by the water, for some kind of grass and aquatic-plants that

works in similar ways).

The

flowers of these types of plants are normally small, insignificant,

without aromas, and they don’t produce nectars or anything that’s

interesting for the majority of insects. Good examples of these plants

are wheat, corn and oats, as well as tobacco and peas and also the oak,

black poplar, linden, elm, walnut and pine trees, among others.

Finally, there is the crossed pollination, pollen from the flowers of a

plant pollinating flowers of other plants of the same species. Those are

the flowers that we all know and appreciate for their colours, aroma and

beauty, the ones that produce nectars to attract and feed a good amount

of small creatures (zoophilla flower), that the plant uses in a perfect

symbiosis to complete its vital circle.

The

crossed pollination of the zoophilla flower is basically done by insects

(entomophilla flower), but also by birds (ornitophilla flower), bats and

other small mammals, even snails and little reptiles.

Among the insects, the bees, the different kinds of honeybees, are

without doubt the most important of them all, the most responsible for

this job, because of their number and how hard they work. The entire

bee-society depends on it; even their own hairy bodies are highly built

up especially for doing this job. Pollen and nectar (honey) is what they

eat and they can’t survive any other way.

Visiting the Hives at “Can Pep Cudulá”

To

speak (I should say to listen and learn about pollination and about bees

in general, Gary and I went in March, the beginning of our spring, about

two weeks before the official date of the real spring, the bee-season,

to visit one of the best beekeepers of the Island and also a good

friend, José Planells “Pep Cudulá”, who lives and keeps some of his

hives in his finca, near Sant Llorenç. (Gary wanted to take photos of

the groundwork with the bees, of the interior of a real hive and of the

work of the beekeepers collecting the swarms, preparing the new panels

for the new season and replacing the old honey-panels)

As

our conversation started about the priceless job that bees do in the

pollination of plants and the enormous benefit that this means, not just

for the plants, but to humans and life in general, Pep Cudulá says with

his good manners and tranquil voice: “Perhaps we will never reach to

understand and appreciate what this little insect has really done and

still does for evolution of life and the progress of the human kind”.

Then

I asked him to clear up why bees are so efficient doing this job. How,

if they fly all over, from plant to plant and from flower to flower can

they be so precise? Why there are not many accidents in the crossing

pollination?

“Once the bees start to collect the nectar and pollen from a specific

kind of flower, normally one of the most plentiful in the area at a

certain time of the year, they continue with the same flower until the

harvest is completed and the honey panels are full”.

“There are some accidents sometimes, for example if you have a field

planted with sweet peppers, and there are near by some plants of

hot-peppers (chiles), because they are the same family of plants, soon

you will have a mixture of hot and sweet peppers, even in the same

plant, this can give you a hot surprise sometimes, specially when you

mean to eat a salad or any other dish made with sweet peppers, this can

happen as well with different kinds of melons and cucumbers, also it is

easy to find bitter almonds in what is supposed to be a sweet almond

tree, but some of these accidents are even profitable and help to form

new varieties. This only happens between plants of the same families and

in general, we can say that bees are far more precise then man as far as

knowing different plants and flowers.

“So

we can also speak of different kinds of honey, depending on which type

of plants the bees have been visiting. The difference in the colour,

aroma, thickness and taste are obvious if you can see and taste them one

by the side of the other, even for the non-experts.

“Most of the honey that we buy in jars at the shops is a mixture of

different types mixed by the industrial experts looking for a specific

quality and homogeneity, as it happens for example with coffee and some

wines. But here, as we don’t produce in industrial ways, our honeys are

all different and we call them by the name of the plant, “rosemary

honey”, “thyme honey”, “azahar honey” (azahar is Spanish for the

orange-tree flower and its aroma. I don’t know if there is an English

word for it). My favourite is the carob-tree-flower honey. I was

honoured with the second prize presenting this type of honey in the

first and only honey show in our Islands.

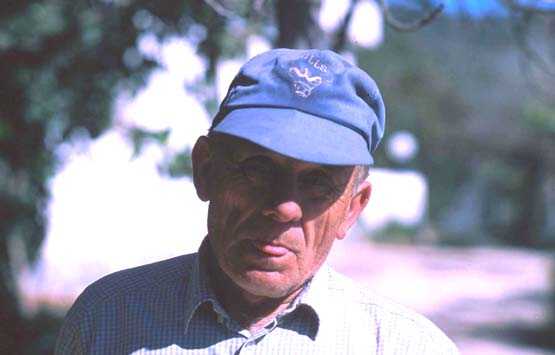

Pep Codulá

Bee Hives at Can Pep Codulá

Pep Codulá on his way to attend the bees

Pep Codulá

checking the honey

|

Pep Codulá

amongst his bees

|

|

|

Pep Codulá

smoking the bees

|

|

All Pictures © Copyright

Gary Hardy (March 2002)

We

shall continue for another week of two with Pep Cudulá and his deep

knowledge about bees and interesting practical lessons about Nature in

general. |